Eye For Film >> Movies >> Burning (2025) Film Review

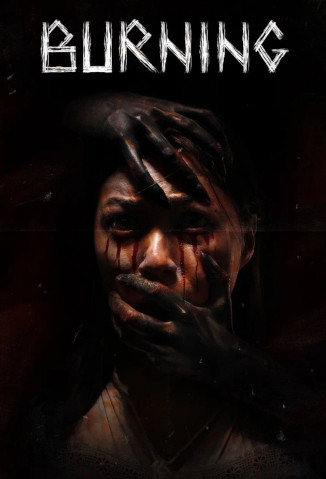

Burning

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Telling and retelling a story from different points of view is by now a well-established trick, its cinematic form most strongly associated with Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. It’s particularly interesting as a mechanism for teasing out social prejudices and exploring the different factors that influence who is deemed most credible. In Kyrgyzstan, where the status of litigants is often a significant factor in the struggle between the law as it is written and the law as it is practised, Radik Eshimov’s Burning invites readers to tease out the truth behind a family tragedy but also to identify the wider social forces that shaped its participants.

The house is on fire. This much, no-one can dispute. It illumines the night sky with its orange glow. Not far away, locals gather in a small shop, where it’s natural conversation fodder. Various different claims are made about what happened there. Some are dismissed out of hand, but three people emerge who purport to know the whole story, and as each one tells it in turn, we will be forced to question and re-question our assumptions.

The facts agreed upon are these. Asel and her husband Marat had a child, Amir, whom they lost in tragic circumstances. Months later, Asel was still struggling to cope, so Marat went away for a couple of days, secretly planning to consult a shaman to see if she might be possessed by a djinn (some traditions holding that djinns prey of those who are emotionally vulnerable. Worried about what she might do in the meantime, he brought in his mother, Farida, to keep an eye on her. The situation deteriorated and, well, you can see the result.

In each of the three tellings, the relationships between these three characters are quite different. Take Farida’s arrival at the house. There is a brief expression of concern, following with Asel rushes to put on a headscarf. Why? She is in her own home, with no male visitors. Is Farida being unreasonable? Is Asel simply making an extra effort to be polite to an older woman who might have more conservative views? Is she hiding something? Later the exorcist will tell Marat that it’s sometimes possible to see from someone’s face when a djinn is present. He will also reveal, however, that he and his team are called out to all sorts of situations, and sometimes there’s no djinn there at all.

Burning screened as part of Fantasia 2025, and along with the supernatural questions raised by the narrative, there’s a small amount of horror-style imagery, as well as scenes which might be triggering to people with experience of distressing familial situations or child loss. What might at first seem to be shocking for the sake of it emerges as necessary grounding in a film that is working towards a much more sophisticated emotional dénouement.

The central performances here are all excellent, despite the significantly different personalities each actor is required to present. There’s also some impressive work from the woman playing Asel’s friend, at the very end, in a postscript which addresses commonplace expressions of social prejudice and the narratives people semi-knowingly invent for themselves to hide behind. It’s an interpretation of what constitutes ‘normal’ that may very well constitute the film’s most chilling moment.

What is it that makes people who love to gossip suddenly clam up and advise one another that it’s better not to get involved? What leads some people to be so sure of themselves, whilst causing others to doubt, or even to try and instill doubt in other people about the evidence of their own eyes? Burning is not just a film about getting to the truth – it’s a film about the construction of truth, and how that is essential to the maintenance of power, and how truth itself can look different with the dawning of a new day.

Reviewed on: 07 Aug 2025